Hawai’i’s waste-to-energy plant isn’t killing two birds with one stone. It’s burning the candle on both ends. By Lauren McNally

Hawai’i’s waste-to-energy plant isn’t killing two birds with one stone. It’s burning the candle on both ends.

By Lauren McNally

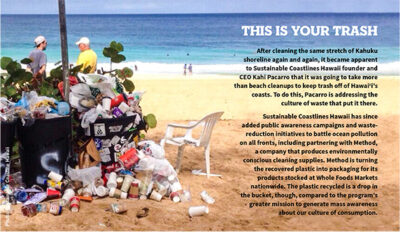

Photo Sustainable Coastlines Hawai’i

Photo: Lauren McNally

Now that H-POWER churns out up to 10 percent of the island’s electricity using municipal waste as fuel, island residents are seeing trash in a new light. Operated by Covanta Honolulu Resource Recovery Venture in a public-private partnership with the City and County of Honolulu, the 28-acre waste-to-energy facility known as the Honolulu Program of Waste Energy Recovery (H-POWER) has incinerated more than 13 million tons of trash since beginning commercial operation at Campbell Industrial Park in 1990.

Although the incinerators are fed up to 3,000 tons of municipal solid waste a day, they still have room to spare. Our trash is trucked in, weighed, dumped and bulldozed amid the clank and hum of intake conveyors that work around the clock to funnel a steady flow of trash into the belly of the beast.

Given that Hawai‘i residents generate 30 percent more trash per person than the average American, waste-to-energy seems like a win-win. Municipal solid waste qualifies as a renewable energy source under the state’s renewable portfolio standard and takes up a fraction of the space at the landfill after it’s incinerated at H-POWER. But burning through our resources is precisely the reason we have a surplus of trash in the first place.

Prior to hopping onboard the waste-to-energy train, Honolulu sent the majority of its trash to the landfill. Landfilling is still the most common form of waste disposal in the United States—abundant land and cheap fossil fuels make it easy for mainland counties to dismiss costly alternatives like incineration. In Honolulu, where energy prices are three times the national average and our municipal waste stream has long threatened to outpace available landfill volume, there’s plenty of incentive to explore other options. Unlike cities on the mainland, we can’t schlep our trash to backcountry landfills in the Midwest once ours are filled to capacity.

“H-POWER is an ideal facility for O‘ahu,” says Markus Owens, public information officer for the Department of Environmental Services. “H-POWER is a form of recycling, turning nearly 800,000 tons of municipal solid waste, which would have normally gone to the landfill, into renewable energy. The city targets only municipal solid waste that is non-recyclable as well as combustible for H-POWER and adheres to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s recommendation of waste-management hierarchy.”

Waste prevention is the EPA’s gold standard for sustainable waste management, followed by reuse, recycling, incineration and landfilling. Hawai‘i’s solid waste management law requires the counties to uphold the same priorities, but incineration has played an increasingly starring role in the City and County of Honolulu’s solid waste management program in recent years. In 2012, the city expanded H-POWER’s annual capacity by 300,000 tons with the addition of a $325 million mass burn combustion unit for processing bulky waste. According to H-POWER facility manager Robert Webster, the 65,000 tires that H-POWER incinerates every year in the new unit are highly toxic when burned alone, so they’re mixed in with other wastes bound for the mass burn combustor, including diverted sewage sludge from an intake station that went into operation in 2015.

Photo: Kevin Whitton

Modern waste-to-energy facilities aren’t the toxin-spewing incinerators of the early 20th century, but there are conflicting views on how safe today’s more stringent standards really are. H-POWER’s mass-burn unit features built-in technology to reduce nitrogen oxide levels, and the facility’s air pollution control system was upgraded in 2008 to comply with federal emission standards. But environmental health isn’t an exact science—emission limits are based on levels achieved at leading facilities, not their effect on public health. Nanoparticles aren’t even a part of the equation yet, so even though microscopic particles such as zinc oxide and titanium dioxide are present in consumer products burned at H-POWER, their emissions aren’t measured, let alone regulated.

Officials aren’t necessarily going in with a fine-tooth comb to ensure compliance, either. The Department of Health averaged less than one inspection per year during H-POWER’s first decade in operation, even when procedures called for quarterly inspections. The department has historically conducted inspections on a less-than-annual basis even after amending its policy to once a year.

But it isn’t only what H-POWER burns that’s cause for concern—it’s what H-POWER isn’t burning. A put-or-pay provision in Covanta’s operating contract guarantees a minimum quantity of waste each year, which the city more than fulfilled prior to the facility’s expansion. The current delivery guarantee of 800,000 tons, however, was established based on how much waste O‘ahu generated pre-recession, so the city has been coming up roughly 100,000 tons short and forking out more than a million dollars each year to cover the deficit. If there’s anything that’ll put a damper on waste-reduction incentives, it’s having to pay for trash we don’t make.

H-POWER is costing the city more than $1 billion dollars in construction, operating and consulting costs, while recycling programs and other waste-diversion initiatives falter from inadequate funding. A city audit released in December found that the Department of Environmental Services administered H-POWER’s expansion and refurbishments without adhering to state and city policies designed to minimize costs. Modifications to the original contracts, which totaled $314 million, established new terms that transfer virtually all financial risk to the city and its taxpayers. The clincher? An amendment that extended Covanta’s operating contract to 2032.

Glass recycling took a major hit in 2014 when the city reduced its payout rate for recovering wine bottles and other non-deposit glass. The city subsidizes non-deposit glass recyclers with funds from a 1.5-cent fee built into the cost of non-deposit glass products, but the fee has failed to cover rising costs. Recyclers can no longer afford to collect and ship the glass to mainland manufacturers, so non-deposit glass from the commercial sector is now landfilled as residue after melting in the burners at H-POWER.

Photo: Kevin Whitton

Fortunately, the logistical hurtles that have hurt glass recycling worldwide have far less traction when it comes to recycling other materials like metal. Seven out of eight Honolulu City Council members backed a recycling subsidy granting recyclers a 25 percent discount on their disposal fees. Mayor Kirk Caldwell vetoed the bill on the grounds that the majority of the $600,000 annual subsidy would go to mainland-based Schnitzer Steel Industries, the state’s largest recycler, but the Council overrode the veto, arguing that local recyclers need all the help they can get to weather the slumped market. The measure originally sought to reinstate a 65 percent discount that ended in 2013.

H-POWER paints a rosy picture of our progress, but the numbers tell a different story. O‘ahu’s 38 percent recycling rate has plateaued over the last five years, and although we’re diverting almost 80 percent of our waste from the landfill when you include waste-to-energy incineration, we’re not producing any less of it than we were five years ago. Incineration reduces our waste to 10 percent of its volume and 25 of its weight, but we’re cheating ourselves by allowing that to stand in for true waste reduction. We’re still disposing ash and residue at Waimanalo Gulch Sanitary Landfill, the island’s only landfill for municipal solid waste. It’s going to catch up with us sooner or later.

Waste-to-energy creates a demand for trash—early adopters like Norway and Denmark have even started importing trash from neighboring countries to generate revenue from energy production. But the megawatts that H-POWER adds to the grid are hardly the best we can do considering Hawai‘i is home to some of the richest sources of renewable energy on the planet—real renewable energy from the sun, wind and waves. Calling our municipal solid waste a renewable energy source is overlooking how much nonrenewable material we consume and subsequently dispose. Most plastics aren’t (or can’t) be recycled due to cost, contamination and sorting and processing demands, and only a third of the recyclable plastics collected curbside even make it into the blue bin. More than 100,000 tons of plastic and other fossil fuel derivatives are incinerated at H-POWER every year, and burning fossil fuels for energy isn’t renewable, no matter how you sort it.

Incineration is a short-term solution to a long-term problem. If we continue to use it as a crutch, then it’s counterproductive to the state’s sustainability initiatives. The last thing Hawai‘i needs is a get-out-of-jail-free card that validates overconsumption. Without legislative policies and city programs in place that increase what we can recycle and reduce what we send to H-POWER, it’s up to us to minimize the amount of waste that makes it to the curb. That’s the nature of the beast—unless we address our culture of waste at the source, we’re only setting ourselves up for an even bigger monster down the line.

Photo: Sustainable Coastline Hawaii